Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon (Das weiße Band, 2009) announces its intentions not with a bang, but with a glacial, unnerving quiet. Subtitled "A German Children’s Story," the film opens on the eve of World War I in the fictional Protestant village of Eichwald, a place rendered in Christian Berger’s pristine, almost painfully sharp black-and-white cinematography. This is not the soft, nostalgic monochrome of memory, but the cold, clinical palette of an archival photograph or a sociological document. From its opening moments, as a tripwire fells the local doctor’s horse in a meticulously orchestrated act of malice, the film establishes itself as a diagnostic. It seeks not to solve a mystery, but to dissect the anatomy of a communal pathology, to map the fertile ground from which a monstrous ideology would later spring.

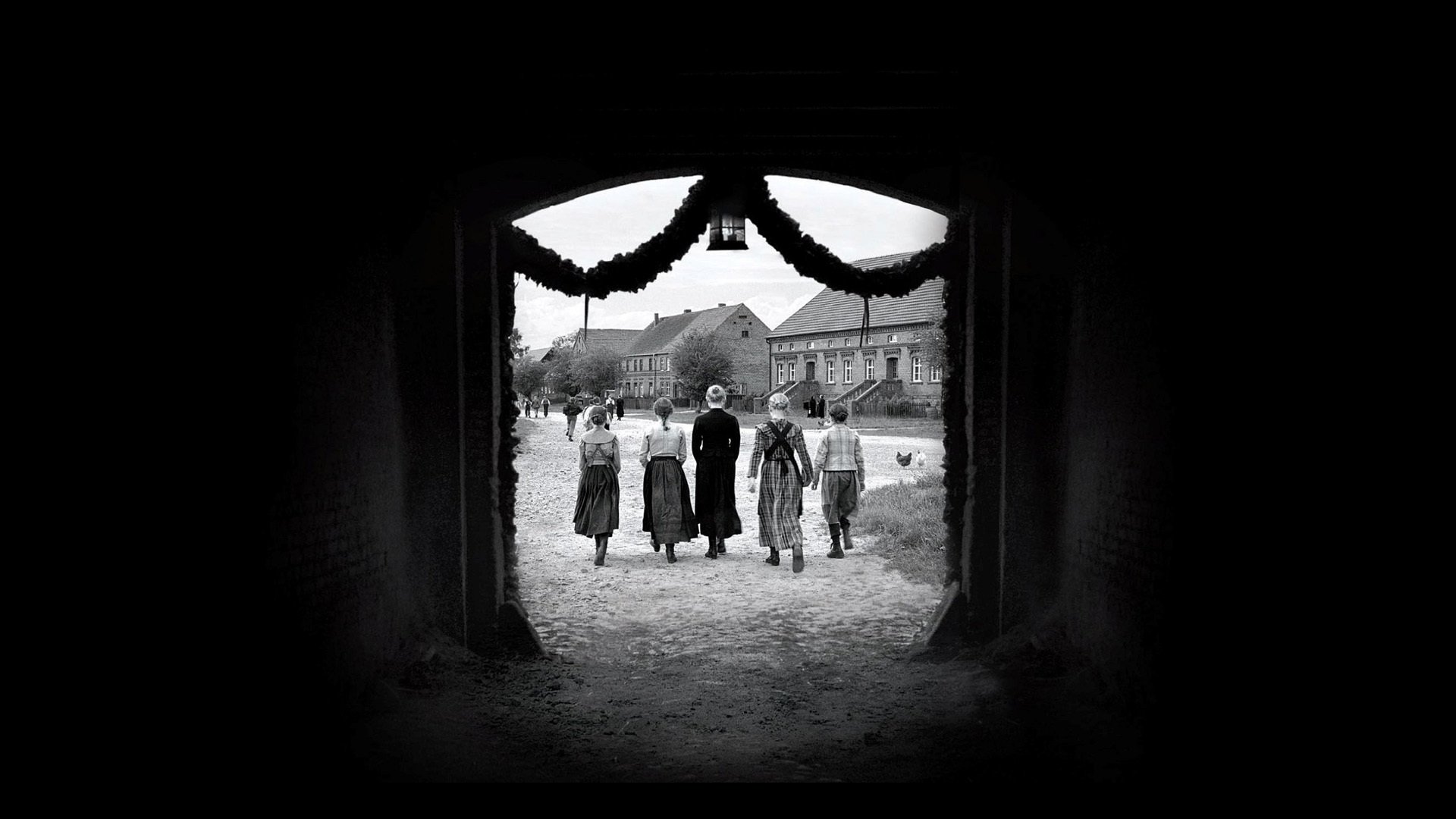

The film’s power lies in its rigorous formalism, a style that mirrors the oppressive social structure it depicts. Haneke’s camera is a patient, detached observer. It maintains a respectful, often theatrical distance, framing characters in doorways or through windows, trapping them within the rigid architecture of their homes and their society. There are few close-ups to solicit empathy; the viewer is denied the comfort of emotional identification. This aesthetic choice is a philosophical statement. By refusing to guide our emotional response, Haneke forces us into the role of an analyst, compelling us to observe the intricate web of power, shame, and punishment that defines Eichwald. The hermetic visual world of the film—its static compositions and deliberate pacing—is the perfect container for the hermetic spiritual world of its inhabitants, a place where grace is absent and judgment is omnipresent.

At the heart of this world are the corrupted pillars of authority: the Baron, the Pastor, and the Doctor. Each represents a form of societal control—feudal, religious, and scientific—and each is revealed to be profoundly rotten. The Pastor, the village’s spiritual guide, enforces a cruel and unforgiving morality, using humiliation as his primary pedagogical tool. The titular white ribbon, which he forces his children to wear as a reminder of their innocence and purity, becomes the film’s central, pernicious symbol. It is not a shield against sin but a brand of it, a constant, visible reminder of potential corruption that breeds resentment and secret rebellion. The Doctor, a man of reason, is privately a figure of monstrous hypocrisy, engaging in the emotional and sexual abuse of his midwife and nursing an incestuous obsession with his own daughter. The Baron dispenses a condescending, detached form of justice, maintaining a social order that benefits only himself.

These adults have cultivated a world built on secrets, lies, and the absolute suppression of natural impulse. It is a world where questions are met with punishment and doubt is seen as a moral failing. And it is in this suffocating environment that the children—the supposed blank slates—become the perfect inheritors and executors of this hidden violence. They are the film’s chilling, unresolved center. Haneke never explicitly confirms their guilt for the escalating series of atrocities—the barn fire, the torture of the Baron’s son, the blinding of a disabled child—but the implication is overwhelming. They are not depicted as individual monsters but as a collective, a nascent organism learning to wield cruelty with ritualistic precision. Their faces, often blank and impassive, reflect back the cold dogmatism of their parents. They have learned their lessons all too well: that violence is a legitimate tool for enforcing a moral order, that punishment can be righteous, and that purity is a concept to be weaponized against the weak.

By refusing to solve the whodunit, Haneke elevates The White Ribbon from a historical drama to a timeless, universal allegory. The film argues that fascism was not an aberration that descended upon Germany, but the logical conclusion of a deeply ingrained cultural sickness—a sickness rooted in patriarchal oppression, poisonous pedagogy, and the perversion of ideals into instruments of control. The eerie silence of the children when confronted by the schoolteacher, the only character who seeks the truth, is the silence of a successful indoctrination. They have formed a secret society with its own brutal code, mirroring the hypocritical society of their elders.

As the Archduke is assassinated and war is declared, the village’s strange incidents are swept aside, forgotten in the tide of a larger, national violence. The sickness that festered in Eichwald is about to go mainstream. The film’s narrator, the aged schoolteacher, admits that his story remains fragmented, its truths uncertain. This final ambiguity is Haneke’s masterstroke. The white ribbon, a symbol of enforced innocence, is a lie that covers a festering wound. The film suggests that any society that builds its foundation on such lies, that prizes ideological purity over human empathy, is merely cultivating the soil for future horrors. It is a profoundly unsettling work, leaving us with the chilling recognition that the children of Eichwald, and the cruel world that shaped them, never truly went away.