In the pristine, hallowed halls of a contemporary art museum in Stockholm, a new installation is being prepared. It is called “The Square.” Its physical form is simple: a 4x4 meter space outlined in light, set into a cobblestone courtyard. Its accompanying text, however, is a grand ideological statement: “The Square is a sanctuary of trust and caring. Within it we all share equal rights and obligations.” It is a beautiful, utopian ideal, a designated zone for altruism in a world of atomized self-interest. It is also the central, damning irony of Ruben Östlund’s The Square, a film that uses this empty space as a moral yardstick against which it measures the profound, comic, and often pathetic failure of its characters to live up to any such ideal.

The film's primary subject is Christian (a perfectly cast Claes Bang), the museum’s handsome, articulate, and deeply ineffectual chief curator. He is the epitome of the liberal cultural elite: he can eloquently discourse on relational aesthetics and disruptive art, yet is utterly paralyzed when confronted with actual human need. Östlund’s satire of the art world is surgically precise and breathtakingly funny. He skewers its pretentious jargon, its absurd installations (like the tidy piles of gravel that are accidentally swept up by the cleaning crew), and its self-congratulatory detachment. This world is a bubble, a hermetically sealed space where compassion is a concept to be curated, not a virtue to be practiced. The film excels in exposing the vast, barren landscape that separates intellectual posturing from genuine ethical engagement.

Christian’s comfortable existence is punctured when his phone and wallet are stolen in an elaborately staged piece of street theatre. His response sets the film's tragicomic narrative in motion. Instead of going to the police, he and a colleague devise a misguided vigilante scheme: they drop a threatening letter into every mailbox of a low-income apartment building where the phone is tracked. This single act of privileged paranoia, born of a desire to assert control, has devastating consequences, primarily for a young immigrant boy who is wrongly accused. Here, the film is at its most potent. Christian, the curator of an exhibit about trust, demonstrates a complete lack of it, choosing aggression and class prejudice over the principles he publicly espouses. His journey is a slow-motion car crash of moral cowardice, a descent into a hell of his own making, paved with good intentions and terrible decisions.

Where the film becomes both formidable and debatable is in Östlund’s signature method: the orchestration of excruciatingly uncomfortable, long-form set pieces. The most notorious of these is the fundraising dinner, where a performance artist named Oleg (Terry Notary), acting as a primal ape, terrorizes the wealthy patrons. The scene is a masterclass in escalating tension. What begins as a provocative performance slowly devolves into a terrifying breakdown of the social contract. The guests, stripped of their civilized veneer, are frozen by fear and a collective inability to intervene. It is a brilliant, unforgettable sequence—a Hobbesian nightmare played out in black tie. And yet, one can’t help but question its purpose. The scene goes on for an almost unbearable length, pushing past social commentary and into the realm of pure, sadistic spectacle. Is Östlund dissecting our passivity, or is he simply reveling in it?

This question hangs over much of The Square. The film is structured as a series of episodic humiliations, not all of which land with the same thematic weight. An awkward, post-coital tug-of-war over a used condom; a press conference constantly interrupted by a man with Tourette’s syndrome; the disastrously misjudged viral marketing campaign for “The Square” that involves blowing up a child beggar. While each scene is a perfectly observed cringe-comedy vignette, their cumulative effect can feel less like a cohesive narrative and more like a scattergun assault. Östlund’s intellectual rigour is undeniable, but his relentless focus on human weakness begins to feel cynical. He is so adept at staging our failures that the film risks becoming a catalogue of them, an intellectual exercise in misanthropy that keeps its subjects, and by extension its audience, at a cool, analytical distance.

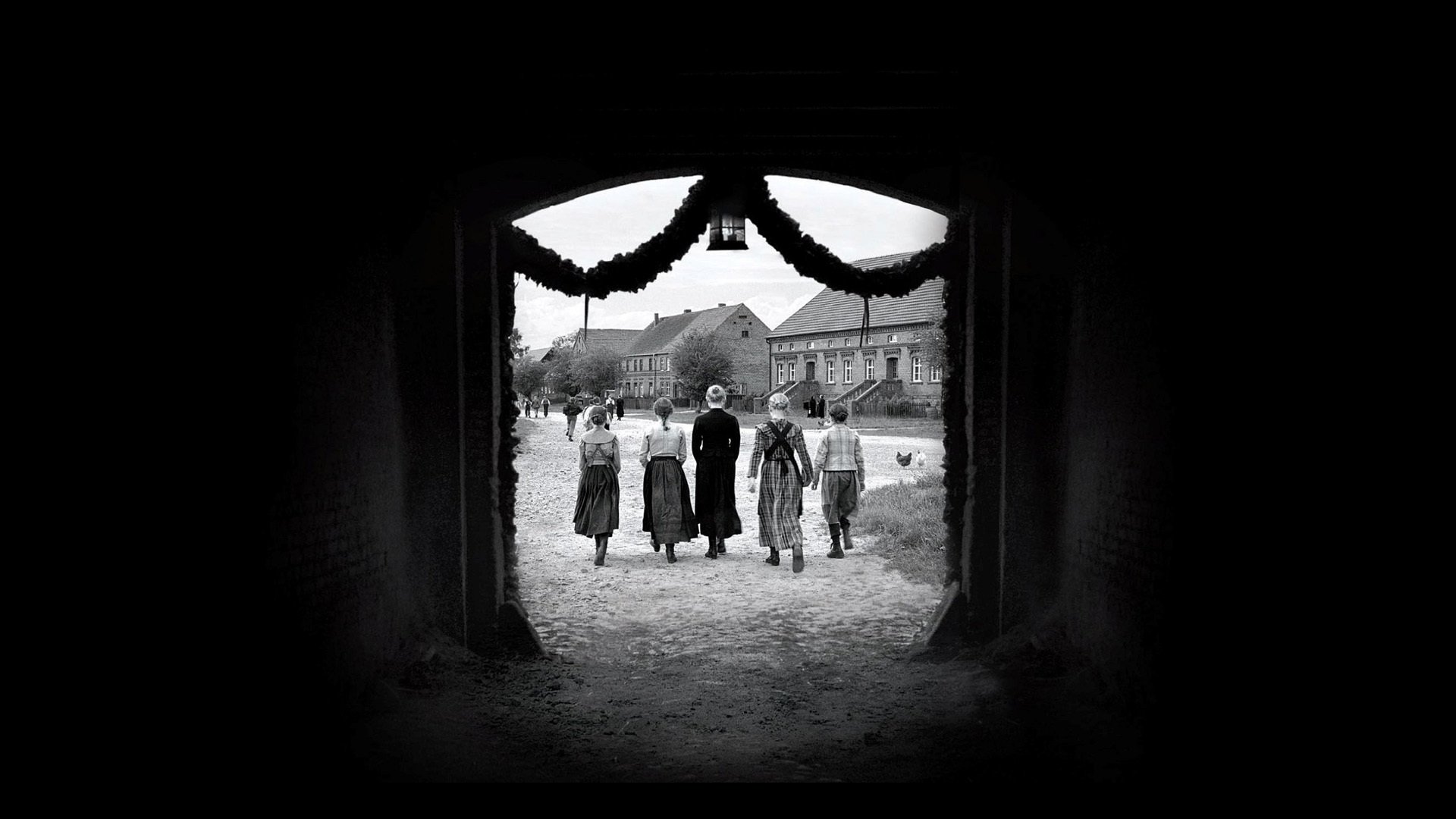

Ultimately, The Square is a brilliant, frustrating, and essential piece of modern cinema. Its diagnosis of the pathologies of our time—the performative altruism, the crisis of masculinity, the breakdown of communal trust—is lethally accurate. But its brilliance is that of a perfectly polished, cold surface. Like the art it satirizes, the film sometimes feels more interested in its own clever concept than in the messy, contradictory humanity it portrays. The final, haunting image is of Christian’s failed attempt to find and apologize to the boy he wronged. The sanctuary of “The Square” remains an empty, theoretical space. No one in the film, least of all its protagonist, is brave or good enough to truly step inside it. Östlund has drawn the box for us, and then masterfully demonstrated that we are all standing on the outside, looking in.